Two Fields Collide in "Scientific Illustration"

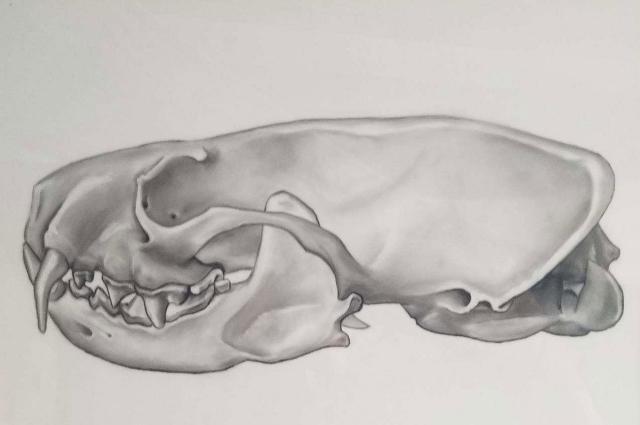

An illustration of a mink skull by Michael Fath using graphite on transparency, a technique students will practice in an upcoming class meeting.

Often people see themselves as either more STEM or more arts-oriented — more analytical or more creative. But how can a scientist use art, or an artist use science? The lines between traditional academic areas have blurred, creating new interdisciplinary fields. In Scientific Illustration, Michael Fath and his students explore the historically significant intersection between visual arts and the sciences.

Fath is well-acquainted with the overlap of art and science. As a researcher, he studies locomotion in fishes in the Tytell Lab. Illustrations have been integral in his science, especially in his Master's work, in which he depicted a new species of the Chondrichthyan class of fish from 320 million years ago named Obruchevodus griffithi. With the practicality of the craft in mind, he teaches the skills of scientific illustration with the goal of fostering his students’ abilities to communicate ideas through images.

Illustration has been essential to the rise of science, acting as a tool for scientists to exhibit their concepts and observations. Some scientists, like Charles Darwin in The Voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle, used it to document their research of new species or novel phenomena. Others, like Leonardo da Vinci, wielded drawings to visualize ideas for inventions and to describe anatomical functions.

No matter the use, though, scientific illustration has been crucial to teaching and learning – visualizations reach a broader audience than words and data. Images have the power to distill complex information into something easily understood. Fath recognizes the demonstrative nature of illustration and its potential:

We're learning classical and modern techniques often used in scientific communications. I would really say that this course is a communication course, which is where I think art and science meet. In both disciplines, the scientist or the artist looks at the world and sees something new and then communicates that new information or vision back to an audience through some medium.

In this already highly interdisciplinary course, the medium is not limited to only paper and pencil. Students use Adobe Illustrator to represent data collected by the Department of Biology, CT scans to digitally dissect animals, watercolor to demonstrate a unique animal behavior, and animations to delineate processes over time. However, these are only a few of the many mediums they will explore throughout the semester.

The students in Scientific Illustration will learn not just the physical skills necessary to make appealing and informative images, but will also discover how to balance their creative and critical thinking. By considering how to condense science into art, they will use both sides of their brain to communicate complicated information effectively, becoming living examples that there can most certainly be artistic scientists and scientific artists.

In a few weeks, we will return to Fath’s class to take a look at some of the work his students have made. Stay tuned!